By Sam Otieno

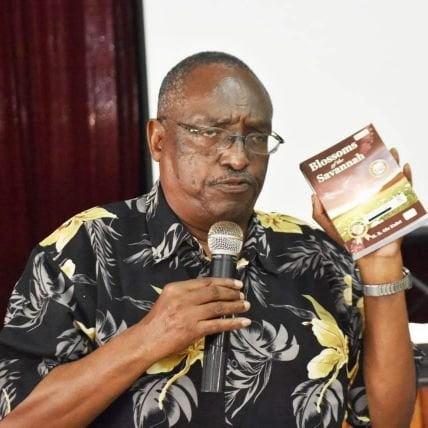

Henry Rufus ole Kulet is one of Kenya’s most decorated writers and a prolific novelist for over four decades since he penned his maiden novel Is It Possible? in 1971.

He has written other nine bestseller novels such as Daughter of Maa (1987), Moran No More (1990) and Vanishing Herds (2011), and won several literary awards such as Jomo Kenyatta Literary Prize for his well-crafted novels: Blossoms of the Savannah (2009) and The Elephant Dance (2017).

His novel, Blossoms of the Savannah, is currently a compulsory set-book in Kenyan secondary schools.

Speaking from his Nakuru home, the seasoned writer recapped his stellar journey in writing and his love for the written word in an interview with this writer.

How has he kept literary fire burning?

“It’s all about interest. My love for literature started in school when my teachers recognised my innate writing ability. They always cheered me to continue writing.”

“When Longman Publishers, which later rebranded to Longhorn Publishers, released my first book Is It Possible?, my interest in writing was further aroused, and I swore never to look back again,” Mr Kulet says.

He writes about the Maa culture with much sensitivity and accuracy of a surgeon’s scalpel.

“I’m a Maasai by birth. I know no other culture better than mine. The kind of informal education I received from my grandma about the Maa way of life endowed me with life as a Maasai.

“I’m so privileged to have written vastly about my culture in writings such as Daughter of Maa and Moran No More,” he says.

When I first read his novel Blossoms of the Savannah, it was so glaring that ole Kulet is a weaverbird of words.

He grew up within the Savanna-land, and most of his books are staged within the vast grassland.

In the book, he piercingly talks about subtle matters like Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and early marriages that have dogged the Maa community for aeons.

“FGM and early marriages are deeply embedded in our culture and may not easily be uprooted. But we have made progress as a greater percentage of our girls can now access boarding schools where they are safe from such barbaric acts,” he says.

He has campaigned against the vices in his books.

“My message about FGM and teen marriages, in the Blossoms of the Savannah, will now reach a wider audience,” he notes.

Having received prestigious literary accolades such as Jomo Kenyatta Literary Prize (thrice) for Blossoms of the Savannah (2009), Vanishing Herds (2013) and The Elephant Dance (2017) before, it did not shock him when Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development (KICD) selected his book to be taught in high schools. Blossoms of the Savannah has been previously studied at O-Level in Tanzania while in Uganda it was picked for A-Level classes.

In 2019, he was honoured by President Uhuru Kenyatta with Elder of the Burning Spear (EBS) medal for his outstanding achievement in writings.

His literary critics such as Prof Evan Mwangi argue that Kulet suffers from cultural and intellectual marginalisation, the reason why his works had not received critical attention from readers.

His take on the aphorism is that he has never been concerned about recognition in his entire writing career, as long as he writes.

“I was previously branded as an ethnic-writer and that my works are mainly premised within the confines of the Maa people,” he retorted.

He continued: “I don’t feel marginalised as a writer. It’s my works that matter and not me. Few people may not know this.”

The fact that his pen has never run out of ink, to him is enough recognition and he is proud of his works receiving some critical attention.

“I strongly feel that Ngugi wa Thiong’o got first to the literary limelight and that’s why his writings have always received much publicity from readers.”

With ten novels tightly under his belt and still keeping his literary eyes on birthing more books; what’s his secret?

“It’s a God-given talent. I always tell people that talent can only be seen when it’s working. It’s your sole responsibility to sharpen and nurture it to fruition. Every book I birth gives me some new synergy to pen another one.”

He believes writers deserve respect and shouldn’t be on the streets giving self-praise about their writings.

“Let the publishers do the sale and marketing part. If you write a good book, it will market itself,” he says.

As we walk around his well-stocked home library, he tells me the reading culture is still not buttressed in the region, mainly owing to our education system, which is examination-oriented.

“People should read for pleasure, but we’re a country that thinks that money should be given priority and not books.”

The writer is a literary enthusiast and a commentator on literature.