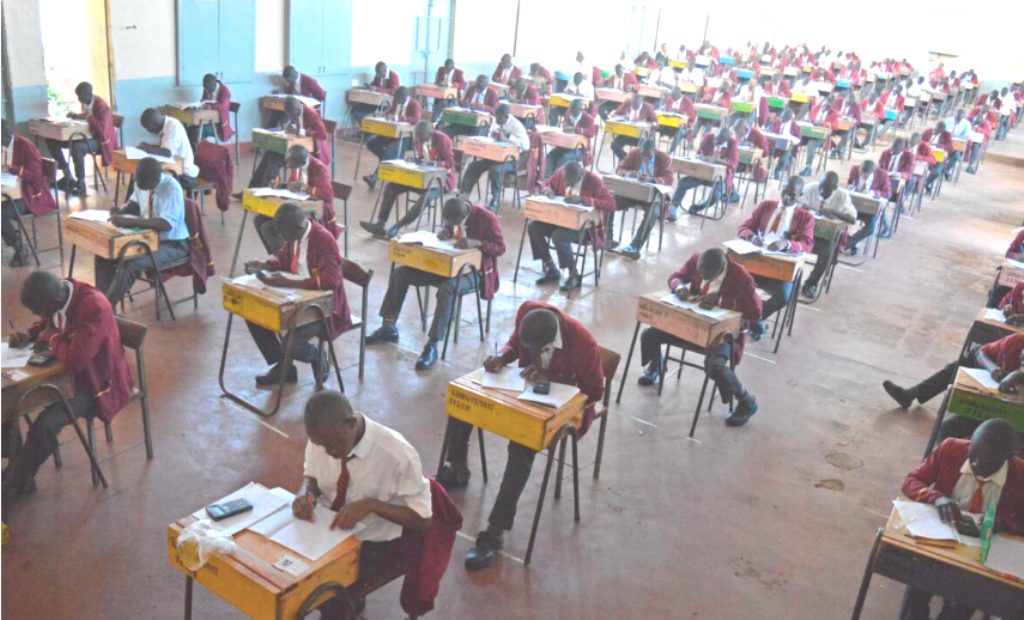

Every year, as Kenya enters the national examination season, the conversation on exam leakage and integrity resurfaces with renewed urgency. The Kenya National Examinations Council (KNEC) puts in place stringent measures to safeguard the entire examination process—from setting to printing and transportation to the designated sub-county containers. These stages are guarded with military precision. The papers are sealed, tracked and handled under multi-agency supervision involving the police, the Ministry of Education, and KNEC officials. Yet, despite all these safeguards, reports of examination irregularities persist. The critical question is: Who compromises the credibility of our national examinations?

To answer that, we must first understand the chain of custody. From setting to printing and packaging, the system remains under KNEC’s direct control. Only vetted and sworn personnel, bound by confidentiality agreements and oaths, handle the exams. There is little room for compromise. Leakages are almost non-existent at this level. Even the transportation to the 290 sub-county containers is done securely, often escorted by armed officers and monitored in real time. Up to this point, integrity remains intact.

The real vulnerability begins after the exams are safely locked in the sub-county containers. These containers—usually stationed at the Deputy County Commissioner’s offices—are opened each morning at exactly 7:00 a.m. by the Sub-County Education Officer, the police and the Centre Managers (who are typically head teachers or principals). Once the examination packages leave these containers, KNEC’s direct control ends. From here on, the papers are in the hands of the very people society entrusts to teach, mentor and guide learners: teachers.

It is a painful but necessary truth: many breaches of examination integrity occur during this last stretch of the chain. The moment those sealed papers are released to Centre Managers and transported to examination centres, the process becomes vulnerable. Teachers, driven by various motives—ranging from pressure to produce high mean scores, competition among schools, financial incentives, or misguided compassion for their students—often become the weakest link.

Some teachers justify their actions by arguing that they are only trying to help their learners “not to be left behind” or to maintain the school’s reputation. Others are lured by money, especially in private institutions where results directly influence enrolment and business survival. In some instances, teachers conspire with examination officers or supervisors to sneak a look at the question papers, send snapshots via mobile phones, or whisper hints during invigilation. In rural areas, there are even reports of teachers writing answers on blackboards before the exams begin or after stepping out under the guise of “assisting candidates.”

The tragedy of it all is that the culprits are not faceless criminals. They are trained educators—custodians of ethics and values. The same professionals who preach honesty, diligence, and hard work in class sometimes betray these very principles when it matters most. The result is a system where the credibility of examination results is questioned, merit is diluted, and the honest student suffers silently while cheats thrive—at least temporarily.

The consequences of these actions go far beyond the examination room. When teachers compromise exams, they erode the moral foundation of the nation’s education system. They produce graduates whose grades do not reflect their true ability, leading to incompetence in universities, colleges, and workplaces. Society ends up with professionals who carry titles but lack the skills and integrity those titles should represent. A nation cannot thrive on forged competence.

But why do teachers engage in such acts despite knowing the risks? The answers are complex. Some cite immense pressure from school boards and parents to produce stellar results. A head teacher whose school posts poor grades risks being transferred, reprimanded or losing sponsorships and parental confidence. Others point to a culture that over-glorifies examination results, reducing the purpose of education to mere grades. In such an environment, integrity becomes expendable.

However, excuses cannot justify betrayal. Teaching is not just a profession; it is a calling rooted in moral responsibility. A teacher who compromises examinations not only fails KNEC or the Ministry of Education but also fails the entire society. When the nation cannot trust its exams, it cannot trust its doctors, engineers, lawyers or leaders of tomorrow.

READ ALSO:

Kisii County Govt to employ 200 ECDE teachers this financial year

The government, to its credit, has continued to strengthen examination security. The multi-agency approach has greatly minimised leakages compared to the dark days of rampant malpractice in the 1990s and early 2000s. Still, enforcement alone is not enough. There must be a deliberate moral reawakening among teachers. The Teachers Service Commission (TSC) should integrate ethics and integrity reinforcement into continuous professional development. Schools should cultivate cultures that celebrate effort, discipline and honesty over mere results.

At the same time, there must be accountability. A teacher who compromises an examination is not a victim of circumstance but an agent of moral decay. Such individuals should face stiff penalties – including deregistration, prosecution, and public naming. Integrity cannot be enforced solely by security personnel; it must be internalised as a non-negotiable professional value.

Parents also share a slice of the blame. Many unconsciously encourage malpractice by exerting unrealistic expectations or offering financial inducements for good results. Some even ask teachers to “assist” their children. This mindset fuels demand for exam cheating. True success should be celebrated when earned honestly, not when stolen through deceit.

Ultimately, safeguarding examination credibility requires collective integrity—from KNEC officials to head teachers, invigilators, parents, and candidates. But if we are to identify the point at which the chain most often breaks, it lies in the hands of teachers—the very people charged with protecting it. They are the custodians of those exams from the moment they leave the sub-county container until the last paper is sealed and returned. If teachers stand firm, no malpractice can occur. If they falter, the system collapses.

As the nation conducts its highest-stakes examinations this year, one truth must be avowed: Kenya’s exam credibility does not crumble in printing presses or armoured trucks—it collapses in classrooms under the watch of teachers who forget their sacred duty. The future of our nation depends not on how tightly we lock the containers but on how strongly we uphold integrity in the hearts of those who open them.

By Ashford Kimani

Ashford teaches English and Literature in Gatundu North Sub-county and serves as Dean of Studies.

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape

>>> Click here to stay ahead with the latest national news.