Every year, as national exams approach, the atmosphere in schools and homes across the country thickens with anxiety. Teachers, parents, and candidates move in a synchronized rhythm of tension, late-night studies, and whispered prayers. The message is clear: this is it. The exam season becomes a national ritual, and for many young people, a psychological battlefield.

But pause for a moment – are exams truly a matter of life and death? Sadly, for too many candidates, they seem to be. Stories abound of students sitting for their national examinations from hospital beds, maternity wards, prison cells, and even under police guard. Each year, we also read the tragic headlines: a candidate who took their own life after performing poorly, or another who collapsed in the exam room from stress and exhaustion. What kind of system celebrates such suffering as resilience?

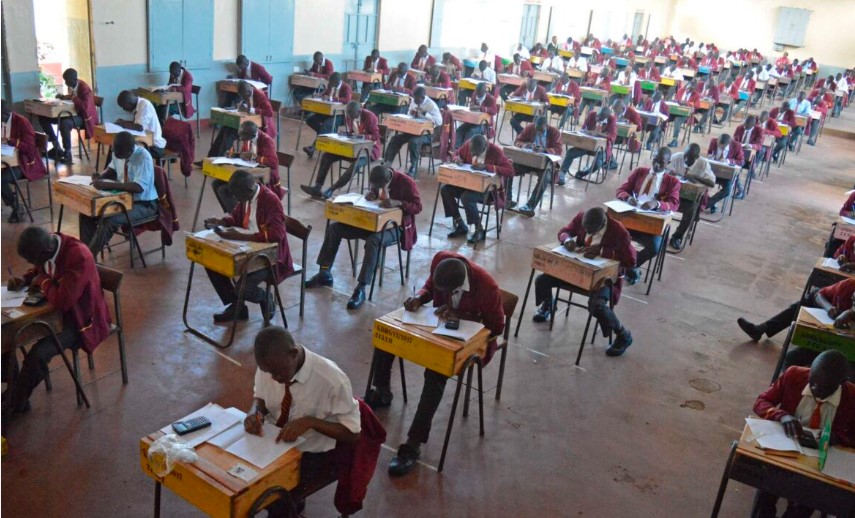

Exams, at their core, were never meant to be instruments of fear or pain. They were designed as a tool to measure learning — not the definition of a learner’s worth. Yet over the decades, our education culture has turned them into a do-or-die moment, a singular gatekeeper to success. In Kenya, as in many other parts of the world, exam results are treated like verdicts in a courtroom. They determine not only which school or course a student joins but also how society views their intelligence, discipline, and potential.

A child who scores top marks is celebrated, photographed, and paraded as a national hero. Meanwhile, those who fail to meet the expected grade are quietly forgotten, sometimes even shamed. This binary culture – success or failure, hero or zero – is psychologically devastating. It has conditioned learners to believe that their entire future depends on a few hours of writing under exam conditions.

When a 17-year-old feels that failing one paper equals the end of their dreams, something has gone terribly wrong. This mindset doesn’t emerge overnight. It is cultivated through years of pressure from parents, teachers, and the system itself. From the time children enter school, they are told to “work hard or perish.” Report cards become emotional weapons.

Family conversations revolve around marks and ranks. And so, by the time a candidate sits for their final examination, they are burdened not just with the weight of academic expectation but with the fear of disappointing everyone they love. For some, that fear becomes unbearable. Cases of suicide linked to poor exam performance are a tragic reminder that we have allowed grades to replace human dignity.

ALSO READ:

Rongo Varsity, St. Dominic students plant over 150 trees during Mazingira Day

Even when we glorify those who sit exams in hospital beds or prisons, we rarely ask the right question: why must someone be forced to prove their academic ability while battling illness, childbirth, or imprisonment? Instead of applauding their determination, we should be interrogating a system that leaves them with no other option. A compassionate education framework should prioritize health, mental wellness, and flexibility – not rigid schedules that treat learners like machines.

Exams are meant to measure learning, not to define learners. Yet we have allowed them to dominate the entire educational experience. This obsession with summative assessment undermines creativity, critical thinking, and emotional intelligence — the very qualities that matter most in the real world. The truth is that intelligence manifests in diverse ways. A learner may not excel in a written test but could be brilliant in music, design, communication, or leadership. Unfortunately, our current examination model rewards conformity and memorization while punishing originality. By reducing education to a race for grades, we rob learners of the joy of discovery and the freedom to fail and try again.

Education should be a journey, not a single moment of judgment. It should nurture the whole person — mind, heart, and spirit. To do that, we must normalize conversations around failure, effort, and growth. Parents must tell their children that it’s okay not to be number one. What matters is that they are learning, trying, and improving. Teachers, too, must shift from being exam-drill sergeants to mentors who recognize the unique strengths of each learner. Counselling and mental health support should be part of every school’s culture, especially during exam seasons. Learners need to hear — from adults they trust — that life does not begin or end with a grade. A C or D does not define destiny; it only describes performance in a particular test, on a particular day.

The crisis of exam pressure is not the fault of students alone. It is a reflection of a society that values outcomes over process, certificates over competence, and rankings over relationships. Parents push because they fear poverty. Teachers push because their professional evaluations are tied to results. The media amplifies it by celebrating top performers as national treasures, ignoring the quiet success stories of perseverance and transformation that happen every day in ordinary classrooms. It is time for a collective change. The Ministry of Education, schools, and parents must work together to restore balance. Continuous assessment, project-based learning, and skill recognition are promising reforms — but they will only work if society itself learns to redefine success.

Exams will always be part of education, but they should never be the whole story. We can build a healthier academic culture by encouraging holistic evaluation that values creativity, empathy, and effort; providing counselling and emotional support before, during, and after exams; training teachers to detect signs of anxiety and depression in learners; creating flexible exam policies for candidates facing emergencies, illness, or childbirth; and promoting open conversations in homes and schools about failure as a natural part of growth.

When a young person understands that their worth goes beyond marks, we liberate them to dream, to learn, and to live fully. Exams are not a matter of life and death – unless we make them so. It is up to us – parents, teachers, policymakers, and the wider society – to ensure that no child ever feels that a failed test equals a failed life. Education should inspire life, not threaten it.

By Ashford Kimani

Ashford teaches English and Literature in Gatundu North Sub-county and serves as Dean of Studies.

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape