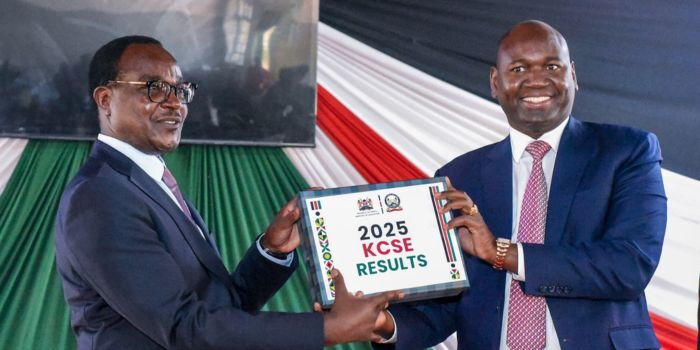

Numbers rarely speak on their own; they demand interpretation. The release of the 2025 Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) results on January 9, 2026, offers such a moment. At face value, the figures suggest progress: more candidates sat the examination, more achieved qualifying grades, and overall performance improved compared to the previous year. Yet beneath the surface, the numbers tell a deeper story about value addition, inequality and the urgent need to rethink how success in education is defined and rewarded.

A total of 993,226 candidates sat the 2025 KCSE, reflecting Kenya’s continued expansion of access to secondary education. Of these, 270,715 attained a mean grade of C+ and above, qualifying for direct entry into university degree programmes. This translates to 27.18 per cent of the candidature, up from 25.53 per cent in 2024. On paper, this improvement is commendable. It suggests incremental gains in teaching, learning and examination integrity. However, it also confirms a long-standing pattern: roughly seven out of every ten candidates do not meet the university entry threshold. Food for thought!

This reality invites an uncomfortable but necessary conversation. For decades, Kenya’s education discourse has been dominated by the pursuit of university admission, often at the expense of alternative pathways. Yet the KCSE numbers remind us that the system is not designed and perhaps should not be expected to funnel the majority into degree programmes. Instead, the results underscore the importance of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), polytechnics, and skills-based institutions as legitimate and valuable destinations for most learners. The challenge lies not in the numbers themselves but in how society interprets and responds to them.

ALSO READ:

Kemei hails impressive KCSE results by Usawa Scholarship beneficiaries

A closer look at school categories reveals even more telling patterns. National schools, which admit learners with the highest primary school scores – often straight As at KCPE – continue to dominate the production of top grades. In 2025, they produced 1,526 of the 1,932 A plains recorded nationwide. Extra-county schools followed closely, buoyed by relatively strong infrastructure, favourable teacher – student ratios, and competitive student intakes. These institutions command prestige, attract resources and remain the preferred choice for high-performing primary school graduates.

Yet here lies one of the most revealing stories in the numbers: educational wastage appears most pronounced in these elite schools. Learners admitted with exceptional entry grades frequently exit with mean grades in the B range. While such outcomes are respectable, they raise critical questions about proportional value addition. If a student enters secondary school as an A candidate and leaves with a B, has the system truly maximised their potential? In environments with superior facilities, experienced teachers, and reputational capital, one would reasonably expect more consistent progression to the highest grades.

Several factors may explain this stagnation. Excessive academic pressure can undermine genuine learning, turning classrooms into high-stress examination factories. Overcrowding, even in prestigious schools, limits personalised attention. Additionally, an institutional obsession with league tables may prioritise maintaining averages over nurturing individual excellence. Whatever the causes, the numbers suggest that elite status does not automatically translate into optimal academic growth.

In contrast, sub-county day schools tell a far more compelling story of transformation. These schools, often community-based and resource-constrained, admit learners with modest primary school results – many with D and E grades. Yet by the time these learners sit KCSE, a significant number have made remarkable academic gains. In 2025, sub-county schools produced 72,699 candidates with C+ and above, outperforming county schools, which recorded 36,600, despite starting with far less advantaged intakes.

This is value addition in its clearest form. It is the story of learners who defy expectations, teachers who go beyond duty and communities that rally around their schools. Smaller class sizes, closer teacher – learner relationships, targeted remedial support and a more nurturing environment often characterise these institutions. Here, progress is measured not by how many As are produced, but by how far a learner has travelled academically. The numbers affirm that excellence can – and does – emerge from the margins.

The disparity between elite and sub-county schools raises fundamental questions about resource allocation and educational priorities. National and extra-county schools receive a disproportionate share of funding, infrastructure investment and experienced personnel. Yet their marginal gains often pale in comparison to the dramatic improvements achieved in under-resourced settings. The KCSE numbers challenge policymakers to reconsider whether current investment patterns truly serve the goal of equitable national development.

ALSO READ:

Kisumu Poly council summons top student leadership for case hearing after suspension

Beyond school categories, the 2025 results also reflect broader systemic trends. Candidates attaining C- and above rose to 507,131, representing 50.92 per cent of the candidature, while those achieving D+ and above increased to 634,082, or 63.67 per cent. These gains suggest gradual improvements in curriculum delivery and learner support. Gender parity was maintained, with female candidates slightly outnumbering males and outperforming them in subjects such as English, Kiswahili and Home Science – an encouraging sign for gender equity in education.

Still, the numbers point to an urgent need to broaden our understanding of success. For the more than 700,000 candidates who did not attain C+, the future must not be framed as failure. TVET institutions offer practical, market-oriented training in fields such as engineering, construction, hospitality, Agriculture and ICT – sectors where skilled labour is in high demand. Strengthening these pathways and according them equal dignity, is essential if education wastage is to be minimised.

Ultimately, the 2025 KCSE numbers tell a story of both promise and paradox. They celebrate progress while exposing inefficiencies. They highlight excellence in unlikely places and complacency in privileged ones. Most importantly, they remind us that education should be judged not merely by raw outcomes, but by the value added to every learner. As Kenya transitions towards competency-based education, the lessons embedded in these numbers should guide a more inclusive, responsive and humane system – one that recognises potential wherever it exists and supports every learner to realise it.

By Ashford Kimani

Ashford Kimani teaches English and Literature in Gatundu North Sub-county and serves as a Dean of Studies

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape