Publishers should be fair to private school parents. That is the cry echoing across many Kenyan homes after another round of school shopping leaves pockets bruised and tempers high. Just this week, a Grade One Mathematics textbook was spotted retailing at Sh920, while a PP1 book was going for Sh850. For many families already battling school fees, transport, uniforms and the ever-expanding list of “mandatory” school items, such prices are not just painful – they are exploitative. And the worst part? Parents have little choice. Once a book appears on the school booklist, it becomes a compulsory purchase.

But how did we get here? Why does a book that the government supplies to public schools at Sh250, or even lower, suddenly cost Sh900 in the open market? Is this a mark-up driven by market forces, or have publishers discovered a captive constituency in private school parents and decided to milk them dry?

A close look at the economics and the moral questions surrounding textbook pricing reveals a troubling picture of an industry that seems to have forgotten its ethical responsibility.

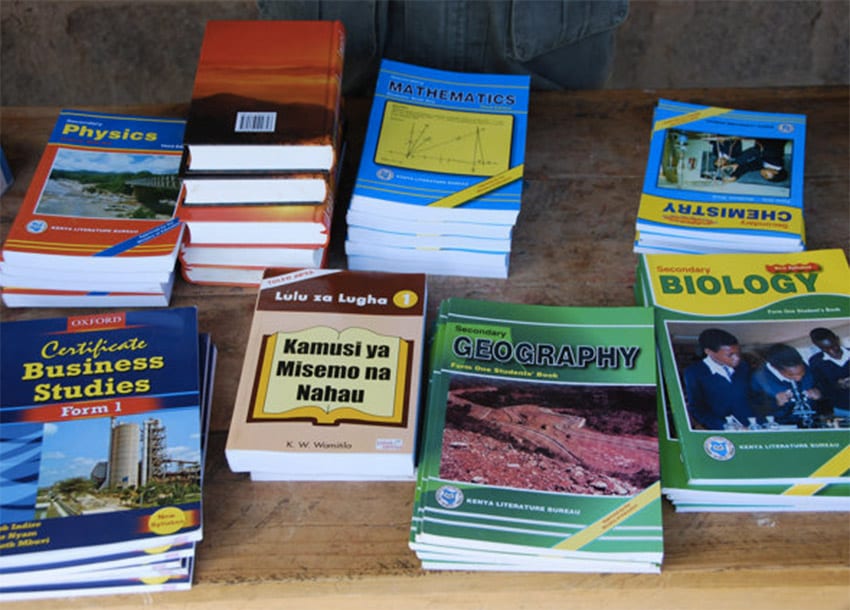

For the past decade, Kenya’s textbook publishing sector has operated on a dual-pricing reality that makes little sense to the ordinary parent. The government, through bulk procurement, purchases millions of textbooks at highly discounted prices – sometimes as low as Sh100 per copy. It is a system that has been praised globally for improving textbook-to-learner ratios in public schools. However, that same book, with the same content, same authors, same paper quality and same curriculum approval, can retail at nearly ten times the government purchase price in the open market.

Publishers argue that bulk procurement and long-term contracts allow the government to negotiate extremely low prices. That is true. Printing 5,000 copies is more expensive per unit than printing 500,000 copies. However, the question remains: does the higher printing cost justify a jump from Sh250 to Sh900? The numbers simply don’t add up.

Even when factoring in distribution, warehousing, editor royalties, VAT, marketing and bookshop margins, a textbook should not be costing nearly a thousand shillings. Unless, of course, someone somewhere is deliberately inflating prices – because they know private school parents have no alternative.

And that is where the problem lies.

READ ALSO:

Private schools do not receive free textbooks from the government. They rely on publishers, distributors and school-booklist systems that create a perfect environment for price manipulation. In many cases, schools recommend specific authors or editions, sometimes even specific bookshops, locking parents into narrow purchasing channels. The result is not a free market; it is a structured monopoly disguised as choice.

Parents feel trapped. They sense – correctly – that they are subsidising the system. When a PP1 parent pays Sh850 for a book the government buys at Sh150, the parent is, effectively, paying for more than the content. They are paying for inefficiencies, inflated margins and in some unfortunate cases, outright greed.

Yet, publishers may be forgetting something: public sentiment is turning. A backlash is brewing, one that could reshape the industry in ways publishers may not like. Several factors signal that the golden age of overpriced textbooks is approaching its dusk.

First, digital learning is slowly but steadily penetrating even the lower levels of schooling. A single tablet loaded with licensed digital textbooks could soon make annual physical purchases redundant. Ed-tech companies are already knocking on the door with cheaper, scalable models.

Second, curriculum developers are increasingly pushing for locally-generated learning materials that are not necessarily produced by major publishers. Teachers now create their own resources, share them online, and sometimes produce higher-quality content at a fraction of the cost. In the long term, this can weaken the dominance of big publishing houses.

Third, parents are becoming more vocal. They are questioning, challenging, and demanding explanations. Social media outrage has already forced several sectors – banking, airlines, supermarkets – to rethink exploitative pricing. Publishers are not immune. If public outcry grows loud enough, the government may step in and regulate prices, just as it regulates drugs, cement or fuel. The publishing sector should be very afraid of that possibility.

Fourth, second-hand textbook trading is becoming more organised. Parents’ groups are forming exchange networks; apps and online marketplaces are emerging. The idea that parents must buy new books every year is evaporating. If publishers continue inflating prices, they may accelerate the very behaviour that destroys their own market.

Publishers must ask themselves: Is short-term profit worth long-term collapse? A publisher friend recently admitted that the high prices worry even insiders. They know it is not sustainable. They know alienating parents will eventually shrink demand. They know a time will come when parents collectively refuse to purchase overpriced text materials.

The truth is simple. Education should not be a financial punishment. A parent sending a six-year-old to school should not have to choose between buying food and buying a PP1 book. This is not just an economic issue; it is a moral one. If the content is the same – same curriculum, same KICD approval – why should learners in public schools receive the books at Sh100 while those in private schools are charged nearly Sh1,000?

Publishers can do better. They can price responsibly, introduce cheaper editions, cap margins and acknowledge the reality that most Kenyan homes are surviving on tight budgets. The purpose of a textbook is to educate a child – not enrich a boardroom.

If nothing changes, the backlash will come. It may not be loud at first, but it will grow. Parents will organise. Schools will revolt. Alternative content providers will rise. Digital substitution will accelerate. Regulators will intervene. And the publishing industry will have no one to blame but itself.

For now, all parents ask for is fairness – not charity, just fairness. A Grade One book should not cost Sh920. A PP1 book should not drain a family’s savings. Publishers must step back, look at the bigger picture and realise that exploiting parents today may cost them an entire industry tomorrow.

The time to rethink textbook pricing is now.

By Ashford Kimani

Ashford teaches English and Literature in Gatundu North Sub-county and serves as Dean of Studies.

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape

>>> Click here to stay ahead with the latest national news.