When the news broke that Albert Ojwang, a teacher from Homabay County, had died in police custody, there was initial confusion, then disbelief, and ultimately a national reckoning. For many Kenyans, it was another disheartening headline in a country where police brutality has become disturbingly normalised.

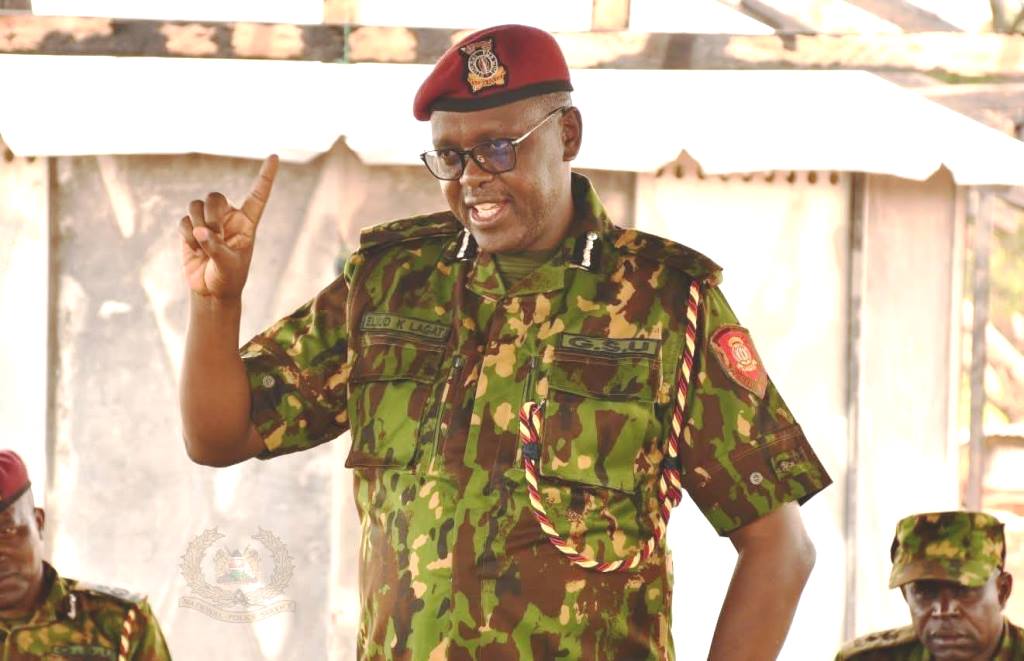

But for one particular group, Kenya’s law students, it was a direct affront not just to justice, but to the very purpose of legal education. In an unprecedented move, the Law Students Association of Kenya (LSAK) released a bold, scathing, and deeply constitutional statement condemning the killing and calling for action against the perpetrators, including the resignation and arrest of Deputy Inspector General Eliud Lang’at. This single act by students has ignited something powerful in the education space, an awakening that law students are not just learners of justice, but guardians of it.

Albert Ojwang was not just a teacher. He was an educator in the truest sense, an individual entrusted with the intellectual and moral growth of the next generation. That he was reportedly arrested for posting on social media, on the platform X formerly Twitter, expressing views deemed offensive to a high-ranking police officer, reflects a national crisis far beyond a single incident. His detention, which ended in his death at Central Police Station, was recorded as a case of self-inflicted injury. But a post-mortem report exposed the truth: multiple injuries to his head, neck compression, and other signs consistent with physical assault. It was torture, not an accident. It was a deliberate violation of his rights, not a tragic misstep. And the law students of Kenya saw this not only as an abuse of power, but as a textbook failure of the rule of law.

READ ALSO:

Chulaimbo High School indefinitely closed due to student unrest, dorm fire

The outrage of law students is grounded in more than emotion. It is anchored in the very fabric of Kenya’s 2010 Constitution. Articles 26 and 29 guarantee the right to life and prohibit torture. Article 25 makes the right to be free from torture non-derogable, meaning it cannot be suspended under any circumstances. Articles 49 and 51 ensure humane treatment of all arrested persons and detainees. These are not abstract principles for students preparing for bar exams; they are living commitments. The moment those rights are violated, every institution of learning, every law faculty, and every law student is implicated. The silence of institutions is no longer defensible when teachers are dying for speaking their truth.

Legal education in Kenya is undergoing a shift, and this moment might define its future. For too long, law students have been perceived as passive observers, preparing for their turn in the corridors of power. However, this tragedy and LSAK’s statement demonstrate that students are now ready to take responsibility. They are not waiting to graduate to start defending the Constitution. They are stepping forward as the living conscience of a legal system in decline.

Their statement was not merely performative. It detailed the legal violations. It named those responsible. It demanded the arrest of those involved, including the officers who carried out the torture. It challenged the silence of the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA), which had failed to act swiftly or publicly. It insisted that educational institutions, the government, and civil society could no longer treat state-sponsored violence as usual.

The education sector, particularly legal education, must understand the gravity of this moment. If educators like Ojwang are not safe in their classrooms or on their phones, then education is no longer a safe space for thought, debate, and dissent. It becomes an environment of fear. Law students are aware of this, which is why their response is revolutionary. They recognise that the same Constitution they study is now a target, that human dignity is no longer protected by default, and that their role as students has transformed into that of advocates, watchdogs, and defenders of democratic values.

But perhaps most importantly, their outrage carries a more profound message: that the Constitution is not a suggestion. It is the supreme law of the land, and no one, regardless of rank or title, is above it.

Deputy Inspector General Eliud Lang’at, according to LSAK’s statement, used the power of the state to pursue a personal vendetta, thereby weaponising the police service against a civilian. That conduct, they argue, not only undermines public trust in law enforcement but also sends a chilling message to teachers, students, and ordinary citizens that their rights are conditional upon who they offend.

Law students refuse to accept this. Their training, their discipline, and their passion for justice have taught them otherwise. They understand that a democracy is only as strong as its ability to protect dissent. That the classroom must be a sanctuary of ideas, and the law must shield, not silence, those who speak truth to power.

The fact that they stood together, unified across universities and regions, to call out this injustice is itself an act of defiance. It is also a redefinition of what it means to be a student. They are no longer merely pursuing academic qualifications; they are now active participants in shaping public morality.

The education community must take note. Schools of law must reinforce the teaching of constitutionalism, not as theory, but as practical empowerment. Human rights law must no longer be confined to pages of textbooks but must be woven into everyday conversations and real-life interventions. The response by LSAK should become a model of legal literacy in action. The training of lawyers must go beyond courtrooms; it must reach into public spaces, online platforms, police stations, and even prisons. The next generation of lawyers must learn not only how to argue the law but how to live it and defend it, especially when it is under attack.

Albert Ojwang’s death is, tragically, not an isolated incident. But it must become a turning point. If the life of an educator can be taken so brutally, and the system chooses silence, then law students and teachers alike must choose resistance. The call for reform cannot remain a slogan. It must become a movement, one led by those who understand the law not as a shield for the powerful but as a sword for the oppressed

It is the responsibility of the legal education system to train warriors for justice, not silent technicians of the state. The streets of Homabay, the cells of Nairobi, and the classrooms of every law school in Kenya are now connected by this moment.

LSAK’s message is clear. We will not be silent. We will remember Albert Ojwang. We will demand accountability. We expect more from IPOA, the police, and the government. And most importantly, we will make legal education count, because when law students speak, it must shake the conscience of the nation.

Let the death of a teacher never again be treated as a footnote. Let this be the generation that turns mourning into movement, grief into justice, and education into the most powerful form of resistance.

By Omwansa Onduko

Onduko is a second-year Law student at Kabarak University

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape

>>> Click here to stay ahead with the latest national news.