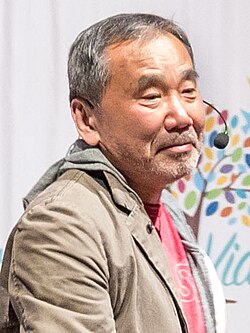

Every October, as the Swedish Academy prepares to reveal the Nobel Prize in Literature, the world of readers, critics and bookmakers hums with excitement. In the swirling sea of predictions, one name has floated to the surface year after year: Haruki Murakami. The Japanese novelist, whose work bridges the dreamlike and the ordinary, has become the perennial “almost laureate,” the writer who seems always on the brink of being called to Stockholm yet somehow never is. For many admirers, the time has come – it is time for Haruki Murakami.

Murakami’s global appeal is unmatched in contemporary fiction. His stories cross borders with quiet ease, drawing readers from Tokyo to Toronto into the melancholy beauty of his universe. Through novels such as Norwegian Wood, Kafka on the Shore, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and 1Q84, he has built an aesthetic that feels both intimate and infinite. His characters – lonely, searching, often accompanied by jazz records or cups of coffee – drift between worlds, blurring the line between the real and the surreal. He gives language to solitude and makes the invisible ache of modern life visible. That universality should matter to a prize that claims to honour the literature of all humanity.

Yet Murakami’s absence from the Nobel roll is not unusual. The history of the award is filled with brilliant omissions. James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, the twin giants of literary modernism, were never honoured. Their innovations in form and consciousness reshaped fiction forever, but the Swedish Academy of their time found them too experimental, too daring. The Nobel Prize, while prestigious, has never been a flawless mirror of literary greatness. It reflects the tastes, politics and sensibilities of its era – sometimes ahead of its time, sometimes stubbornly behind it.

Consider the story of Johannes V. Jensen, the Danish writer who waited through almost two decades and more than fifty nominations before finally hearing his name in 1944. His long wait shows that the Nobel is as much about timing as about talent. Greatness alone is rarely enough; a writer must also align with the moment’s mood. Perhaps Murakami’s moment is approaching – perhaps the Academy is finally ready to embrace a voice that has already embraced the world.

ALSO READ:

Why book industry must look beyond textbook market to survive

One reason often offered for his exclusion is popularity. Murakami sells millions of copies, fills auditoriums, and inspires pilgrimages to the settings of his novels. Some critics suspect that his fame makes him less “serious,” as though mass readership somehow disqualifies artistry. Yet popularity and profundity need not be enemies. Gabriel García Márquez was both a bestseller and a Nobel laureate. So was Toni Morrison. Murakami’s reach does not dilute his art; it magnifies its resonance. His work’s accessibility is not simplification – it is empathy, rendered with precision and restraint.

Another argument claims that Murakami’s fiction is too inward, too detached from politics or social struggle. But this misunderstands his quiet radicalism. Beneath the calm surfaces of his narratives runs a deep critique of alienation, consumerism, and loss of human connection in a mechanised age. His worlds are full of people who have vanished, of systems that grind individuality into dust. Through metaphor rather than manifesto, he captures the psychological fractures of our time. Like Franz Kafka, one of his literary ancestors, Murakami transforms personal unease into a universal condition.

The Nobel Prize in Literature has lately shown signs of widening its gaze. In recent years, it has celebrated writers like Olga Tokarczuk, whose work bends time and form, and Abdulrazak Gurnah, who gives voice to displacement and exile. This suggests that the Academy is listening more closely to global narratives of identity and belonging. Murakami, whose fiction speaks to the quiet dislocations of the soul in a globalised world, fits that evolution perfectly. His art, rooted in Japan yet fluent in the emotional dialect of the planet, bridges East and West without belonging wholly to either.

To honour Murakami would be to recognise the literary shape of the 21st century – fluid, hybrid, introspective, and global. It would also acknowledge how literature has expanded beyond national borders to speak to shared anxieties: isolation, memory and the search for meaning amid noise. Few writers have mapped those emotional geographies as patiently as Murakami has.

ALSO READ:

Guidance and Counselling teachers call on TSC to end years of professional neglect

And yet, there is something almost poetic in his long wait. Like one of his own protagonists – a quiet, persistent man who wanders through mysterious corridors in search of a vanished truth – Murakami seems content to let time take its course. When asked about the Nobel, he typically shrugs it off: “If I get it, I get it. If not, it’s okay.” His detachment echoes the Buddhist calm that runs beneath his fiction – the sense that recognition, like everything else, is transient.

Still, the world’s readers feel otherwise. They sense that Murakami’s moment would not merely crown an individual career but symbolise something larger: the triumph of literature that unites imagination with empathy. In an era when digital distraction threatens attention and compassion alike, Murakami’s patient storytelling – his insistence that we listen, reflect and dream – feels revolutionary.

The Nobel Prize cannot confer greatness; it can only acknowledge it. But sometimes acknowledgment matters – not for the writer, who will keep writing, but for the readers who need to see their experience reflected in the canon of the world’s best. For them and for literature itself, it is time for Haruki Murakami.

By Ashford Kimani

Ashford teaches English and Literature in Gatundu North Sub-county and serves as Dean of Studies.

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape