Across the world, countless students have had their memories of subjects they once loved tarnished—or even ruined—by teachers whose words or methods left lasting psychological scars. These are not isolated stories; they are echoed from classrooms in Kenya to high schools in the United States, from rural India to Europe, and beyond. What these narratives share is a common thread: the subject itself was not the problem, but the teaching experience became the reason students turned away from an entire field of knowledge.

In the United States, a widely circulated account comes from a student named Carla, who shared her story in a national education magazine. She excelled in mathematics through primary school and enjoyed solving problems for fun. But when she reached high school, her algebra teacher publicly scolded her for asking a question he deemed “obvious.” He made her stand in front of the class while he explained why her question was beneath the level of the class. Though he later apologised, Carla said that moment changed everything. Math became a source of anxiety rather than curiosity. She avoided advanced math classes, and by the time she entered college, she had switched her major entirely, leaving behind a subject she once loved and could have pursued professionally.

In the United Kingdom, stories of negative experiences in science classes have similarly shaped academic trajectories. A student named James recounted how his secondary school physics teacher repeatedly told him he wouldn’t grasp complex concepts because of a perceived lack of “scientific instinct.” The teacher’s dismissive comments were made in front of classmates, breeding embarrassment and self-doubt. James said that by the time he reached his GCSE exams, he had thoroughly checked out of science, believing he was “not cut out for it.” Decades later, now in his thirties, he still remembers the teacher’s words and the sense of dread he felt every time he saw a physics textbook.

In India, where competition and academic success are intensely emphasized, the stories are often tied to high-stakes exams. A teenager named Priya shared her experience with her English literature teacher in a popular online forum. As an enthusiastic reader with a love for poetry, Priya once imagined studying literature at university. Her teacher, however, treated her questions with contempt, repeatedly calling her interpretations “childish” and “unsophisticated.” Instead of nurturing her love for reading, the teacher evaluated responses solely on rigid mark-oriented criteria, dismissing imaginative thinking as irrelevant. By the time the board exams approached, Priya had stopped reading creative literature altogether. She focused only on exam-focused summaries and lost the joy that once drew her to books.

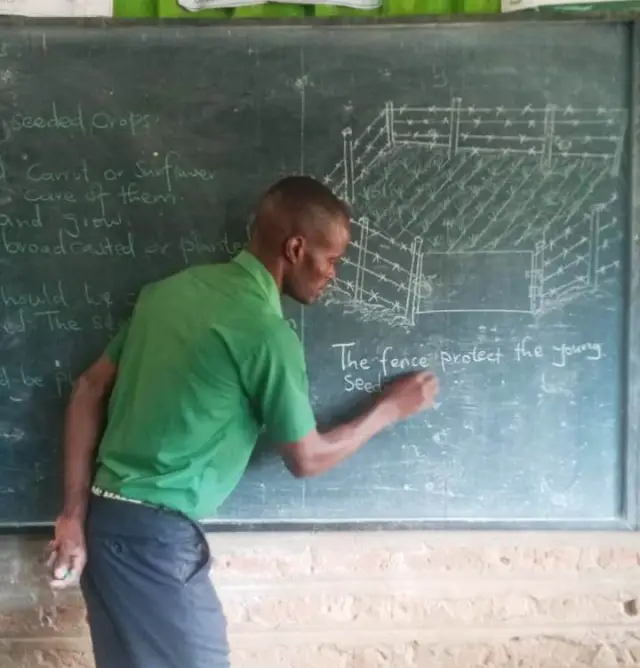

Across sub-Saharan Africa, including Kenya, similar experiences are reported. One student, now a teacher herself, wrote about her early encounters with English language instruction. At her primary school, her teacher publicly penalised students for incorrect pronunciation, using mockery as a disciplinary tool. This created an environment where many students became fearful of speaking up, even when they knew the answers. She explained that many of her classmates grew to hate English, not because of its complexity but because it became associated with humiliation and fear. Only years later, when she encountered teachers who encouraged dialogue and celebrated minor improvements, did she begin to reclaim her relationship with the subject.

In Japan, stories of stern mathematics teachers also surface frequently. A young woman named Aiko described how her middle school math teacher would slam textbooks and yell at students who did not complete homework on time. Despite her genuine effort, Aiko often fell short of perfection and felt consistently shamed. She associated math with loud reprimands and dread, a feeling that persisted into adulthood whenever she needed to help her own children with homework.

READ ALSO:

Uhuru Kenyatta attends Kabarak University’s 21st graduation ceremony as chief guest

The damage done by negative teaching experiences is not limited to academic outcomes; it can extend into professional identity and emotional well-being. In Australia, a university student named Liam recounted how his high school science teacher unfavourably compared his laboratory performance with that of his peers in front of the whole class. “You’ll never make it in science,” the teacher told him. Not only did Liam switch out of science subjects, but he also lost confidence in his ability to engage in any analytical field. He described years of imposter syndrome that followed him through higher education and into his early career, long after he had left that classroom.

These stories underscore a broader pattern: teachers who rely on fear, humiliation, or ridicule as tools of classroom control often leave behind students who associate entire disciplines with negative emotions rather than intellectual curiosity. What is particularly tragic is that these students often had potential—talent that was never fulfilled simply because of the social context in which they learned.

Carol Dweck’s research on mindset offers insight into this phenomenon. Students develop either a fixed mindset, in which they believe their abilities are static, or a growth mindset, in which they see effort and learning as paths to improvement. Teachers who focus on labelling students—explicitly or implicitly—tend to foster fixed mindsets. When a student hears “You’re just not good at this,” that belief becomes internalised, blocking resilience and curiosity. In contrast, positive teaching approaches that emphasise feedback, effort, and understanding create an environment where students feel safe to take intellectual risks. The absence of such support can have the opposite effect: students withdraw, disengage, and sometimes abandon whole fields of study.

In Kenya, educators working with the Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC) have observed similar dynamics. CBC encourages a holistic view of learning, focusing on learners’ competencies and self-directed progress. Adverse experiences that focus on rote repetition or punitive assessments directly contradict the goals of competency development. Teachers who fail to shift away from traditional, lecture-based, authoritative methods may inadvertently reinforce the same negative experiences that drive students away from subjects they might otherwise embrace.

These global cases illustrate that while curricula and cultures vary, the human dynamics of the classroom share commonalities. The power imbalance between teacher and student means that a single moment—an offhand comment, a public correction, a dismissive response—can have outsized influence on a learner’s educational journey. At its best, teaching opens windows; at its worst, it can close doors and lock them.

Yet, it is important to recognise that these stories often have a secondary arc: many adults rediscover subjects later, sometimes through supportive mentors, self-directed study, or environments that honour curiosity. Their early hurt does not vanish, but it can be transformed. These narratives are testaments not just to the harm that poor teaching can cause, but also to the resilience of learners and the profound influence that compassionate, reflective teachers can have on restoring confidence and love for learning.

By Ashford Kimani

Ashford teaches English and Literature in Gatundu North Sub-county and serves as Dean of Studies.

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape

>>> Click here to stay ahead with the latest national news.