It’s 4 p.m. in the quiet village of Kibiko, Kajiado West. The sun dips low, painting the Ngong hills gold as children rush home from school, their laughter echoing along the dusty paths.

Five year old Sharon Senteu bursts through the door, her small school bag bouncing on her back. Hungry after a long day, she grabs a cup of porridge from the kitchen. Halfway through drinking, she suddenly remembers something.

With her tiny hands, she pulls a tattered exercise book from her bag and hands it to her mother.

“Mom, homework. Teacher said I didn’t get it right yesterday,” she says softly, her eyes filled with hope.

Her mother, Nancy Naipanoi, hesitates. She flips through the book filled with drawings and numbers strange symbols she can hardly understand. Embarrassed, she makes random markings, hands the book back, and says firmly.

“Give it to your father to do. This is teachers’ work, not parents’. Tell your teacher that!” she tells her with a sharp tone.

Behind her sharp tone lies quiet frustration. Naipanoi never went to school. Reading and writing remain a mystery, and helping her daughter with homework feels like an impossible task.

ALSO READ;

Alupe University suspends classes for Fresher’s Day celebrations

CBC: Curriculum that demands more from parents

Naipanoi’s story mirrors that of thousands of parents across Kenya who are struggling to keep up with the Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC), a system that expects parents to be active partners in their children’s education.

Under CBC, Parental Empowerment and Engagement (PEE) is one of the key pillars. Parents are expected to help with home assignments and projects, collaborate with teachers, provide moral and material support, and model positive values at home.

But for parents like Naipanoi, this expectation feels unrealistic.

“I don’t understand what parental engagement means,” she admits, stating that no one has ever taken her through that and they were left out.

“My role is to pay school fees. All these assignments should be done by teachers, schools should also stop asking children to bring materials from home it’s too expensive.”

When CBC was introduced, one critical gap was left unaddressed, how to include parents who cannot read or write. Many, like Naipanoi, genuinely want the best for their children but feel shut out by a system that assumes every home has a literate adult ready to help.

For little Sharon, a simple homework assignment exposes a much deeper issue, how a well-intentioned education reform can leave some families behind.

ALSO READ;

JSS teachers sue state over plan to place them under primary heads

Fighting back through learning

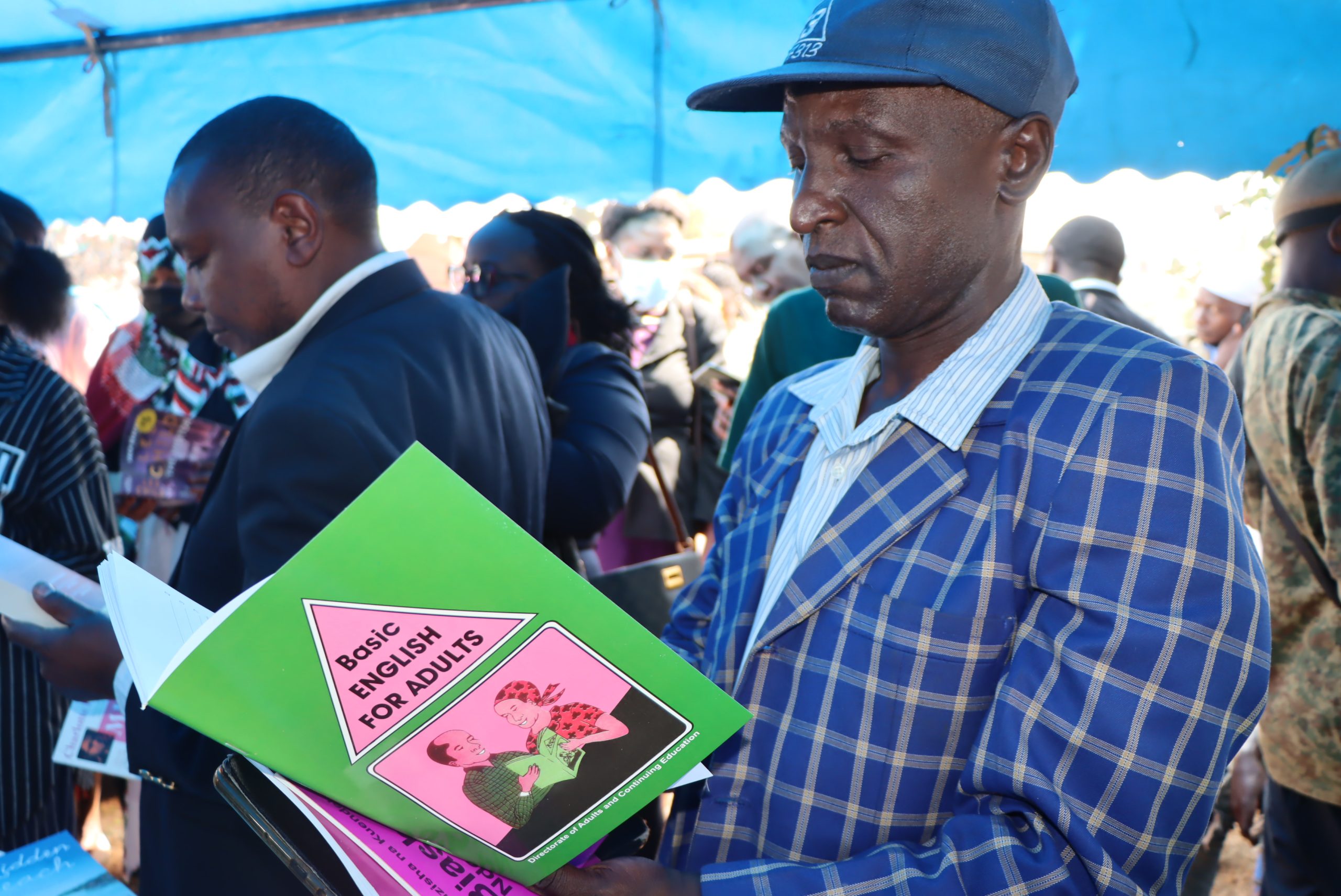

However, in Nairobi’s Westlands Constituency, some parents are refusing to be left behind. Their weapons are not protests or complaints but textbooks, pencils, and adult education classes.

Earlier this year, they proudly celebrated International Literacy Day on September 8, 2025, clutching their well-earned certificates.

One of them, Teresia Mobai, 59 years, dropped out of school at a young age due to poverty. Today, she is among dozens of parents who have returned to class, determined to change their stories and those of their children.

“I have seen the true importance of education, I used to struggle to help my children with school projects. Sometimes I would hire people to do it, but it was expensive and I didn’t even know if they were qualified,” she says, smiling. Now, her eyes shine with pride.

“I can read and write. I can even speak a little English,” she says with a smile. “I tell other mothers, go back to school. The world is moving very fast don’t be left behind.”

At 63, Nela Murungi from Kawangware, Nairobi, is another shining example. She dropped out of school when she was young, but after enrolling in an adult education program, she says her life has changed completely.

“I run a small business, and before, I used to struggle when doing transactions. Now I can handle them easily,” she says. She celebrates the day with a certificate, a sign of hope.

“I’m also a church leader, and the sermons are in English, i used to feel left out, now, I can follow everything.”

Today, Murungi confidently chats with her children on WhatsApp, helps her grandchildren with homework, and manages her business better than ever.

“I may be old,” she says, laughing softly, “but as long as you have eyes and ears, go back to school. You’ll see the fruits later. Age has no meaning when it comes to education.”

She plans to continue learning and enroll in more advanced classes.

Nelias Nohumba, a trainer at Dadas Community Education Centre, says teaching adults comes with unique challenges.

ALSO READ;

Litein Boys’ candidates back for KCSE after weeks of uncertainty

“Many of them have jobs and families, so finding time for classes can be difficult,” she explains. They have to leave their businesses for some hours to access education which they found to be their only hope.

“But their determination is inspiring. We not only teach literacy, we also train them in income generating activities to improve their livelihoods,”she says.

She adds that more parents are now showing interest in joining adult education programs after realizing how crucial literacy is in supporting their children’s learning.

Back in Kajiado, Sharon still brings home her homework and though her mother, Naipanoi, cannot yet help her, stories like Teresia’s and Murungi’s offer a glimpse of hope.

With more parents choosing to learn, a new generation of mothers and fathers is beginning to bridge the education gap one class, one word, and one homework page at a time.

By Obegi Malack

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape