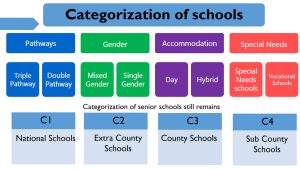

For decades – since the colonial era – elite secondary schools, formerly known as National Schools and now classified as C1 schools under Kenya’s Competency-Based Education system, have dominated national examination performance.

Year after year, they top ranking tables and command public admiration. The prevailing belief has been simple: these schools excel because they admit the brightest learners and have the best systems to polish them further.

But as Kenya fully transitions into the Competency-Based Education (CBE), it is time to interrogate that assumption more courageously.

At the heart of CBE lies a bold national commitment: to nurture every learner’s potential. Not a select few. Not only the already advantaged. Every learner. That promise demands that we rethink how opportunity is distributed within our education system.

Learners in Kenya begin their academic journeys from profoundly unequal starting points. Some attend well-resourced private academies and urban public schools with stable electricity, internet connectivity, fully equipped laboratories, stocked libraries, adequate teacher staffing, and supportive home environments. Their exposure is broad. Their learning disruptions are minimal. Their academic support structures are strong.

Others study in rural or marginalized schools facing teacher shortages, overcrowded classrooms, inadequate textbooks, limited infrastructure, and little technological access. Some walk long distances to school. Some revise under kerosene lamps. Some share materials meant for many.

Yet when assessment results are released—whether at KPSEA, KJSEA, or other transition points—these learners are ranked together as though they competed on equal ground. They did not.

ALSO READ:

Schools urged to meet MoE’s KSSSA registration deadline ahead of Narok County games

We cannot allow a system where only learners with EE join national C1 schools while those who scored BE are left in village schools with limited facilities. That is not equity. That is the preservation of advantage.

A learner who scored BE in an under-resourced rural school may possess equal—or even greater—raw potential than a learner who scored EE in a fully equipped urban academy. The difference may lie not in intelligence, but in exposure, consistency of instruction, and access to learning tools.

Academic grades often measure opportunity as much as they measure ability.

If C1 schools continue admitting almost exclusively top scorers, we risk turning them into institutions that reward prior privilege rather than expand opportunity. The CBE framework was not introduced merely to rename classes or redesign assessments; it was introduced to correct structural imbalances and focus on holistic growth.

Senior School under CBE is intended to be a stage of specialization and talent development. It is where learners refine their strengths in sciences, humanities, creative arts, sports, and technical pathways. If this is the vision, then access to the strongest environments should not be restricted to those who are already thriving.

C1 schools have the infrastructure, experienced teachers, expansive co-curricular programmes, and mentorship networks capable of transforming lives. For a learner who has shown resilience and promise despite systemic barriers, such an environment can unlock extraordinary outcomes.

High-performing learners who scored EE will likely succeed in any reasonably supportive environment because they are already self-driven and academically strong. Placing them exclusively in elite institutions may reinforce existing advantages rather than broaden access.

The deeper question is this: Are C1 schools meant to reward prior achievement alone, or to serve as engines of mobility and transformation?

ALSO READ:

TSC to create database of teachers excelling in co-curricular activities

Merit should never be ignored. Excellence matters. Standards matter. But merit must be interpreted within context. A BE earned in hardship may represent greater academic effort and potential than an EE earned in abundance.

Internationally, equitable education systems recognise contextual performance and deliberately create pathways for learners from disadvantaged backgrounds to access top-tier institutions. The aim is not to dilute standards, but to democratize excellence.

If CBE is to fulfil its promise, admission policies for C1 schools must align with its philosophy. Contextual placement models, affirmative considerations, and equity mechanisms should be strengthened so that access reflects both performance and potential.

Education reform is not only about changing syllabi or assessment codes; it is about structural justice. If we maintain selection systems rooted purely in exam-era thinking, we will reproduce the same inequalities under a different curriculum name.

Kenya stands at a defining moment. C1 schools should not be exclusive preserves for those who have already excelled. They should be transformative spaces for those whose potential—given the right environment—can redefine excellence itself.

We cannot allow a future where opportunity flows only to those who already had it. If Competency-Based Education means anything, it must mean this: talent exists everywhere, and access must follow it.

By Polycap Ateto

Polycap is a ranking teacher and a CBE champion.

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape

>>> Click here to stay ahead with the latest national news.