Every year, the release of KCSE results follows the same script. Names trend, mean scores dominate headlines, schools posture, parents compare, and candidates are quickly sorted into invisible boxes marked success and failure. Celebration spills onto roads and social media, while disappointment retreats into silence. In the noise, one thing is often lost: perspective.

KCSE results matter. No sensible person denies that. They open doors, shape opportunities, and influence immediate choices. But what they do not do is pronounce a final judgement on a young person’s life. Treating them as such is not only misleading—it is dangerous.

Let us begin with honesty. KCSE is a high-stakes exam taken at a very young age, under uneven conditions, in a system that rewards a narrow definition of intelligence. It measures how well a learner mastered examinable content, within a fixed time, under pressure. It does not measure creativity, resilience, emotional intelligence, ethics, curiosity, leadership, or practical ability. Yet year after year, we behave as if it does.

For candidates who performed well, the national applause is loud and immediate. That is fine. Hard work deserves recognition. But here is the uncomfortable truth we rarely say aloud: top grades do not guarantee an easy life. Many straight-A students later struggle when success stops being structured, supervised, and predictable. Life does not issue marking schemes. It rewards adaptability, teamwork, humility, and persistence—qualities exams barely test.

Over-celebration also carries risk. We have seen it before: reckless partying, substance abuse, poor decisions made in the glow of praise. A good result should not mark the beginning of indiscipline. It should mark the beginning of maturity. Excellence is not fragile, but arrogance is.

Then there is the other side of the results—the side we do not like to talk about. The quiet homes. The switched-off phones. The learners staring at certificates that do not reflect their hopes. For them, the emotional weight can be crushing. Society has a habit of equating grades with worth, and young people absorb that message quickly. This is where damage is done.

A learner who scores below expectations is not a failure. They are a learner whose strengths may not fit neatly into an exam system. Some mature later. Some thrive practically. Some simply needed a different environment or support. Yet we brand them early, and some never recover their confidence. In extreme cases, the shame turns into depression, withdrawal, or self-harm. That should trouble us deeply.

ALSO READ:

Parents, at this moment, hold enormous power. A single reaction can either stabilise or scar a child. Anger, ridicule, threats, and comparisons help no one. Your child already knows the result. What they need now is reassurance that their value has not changed. This is not the time to perform parental disappointment. It is the time to plan calmly. And planning requires broader thinking.

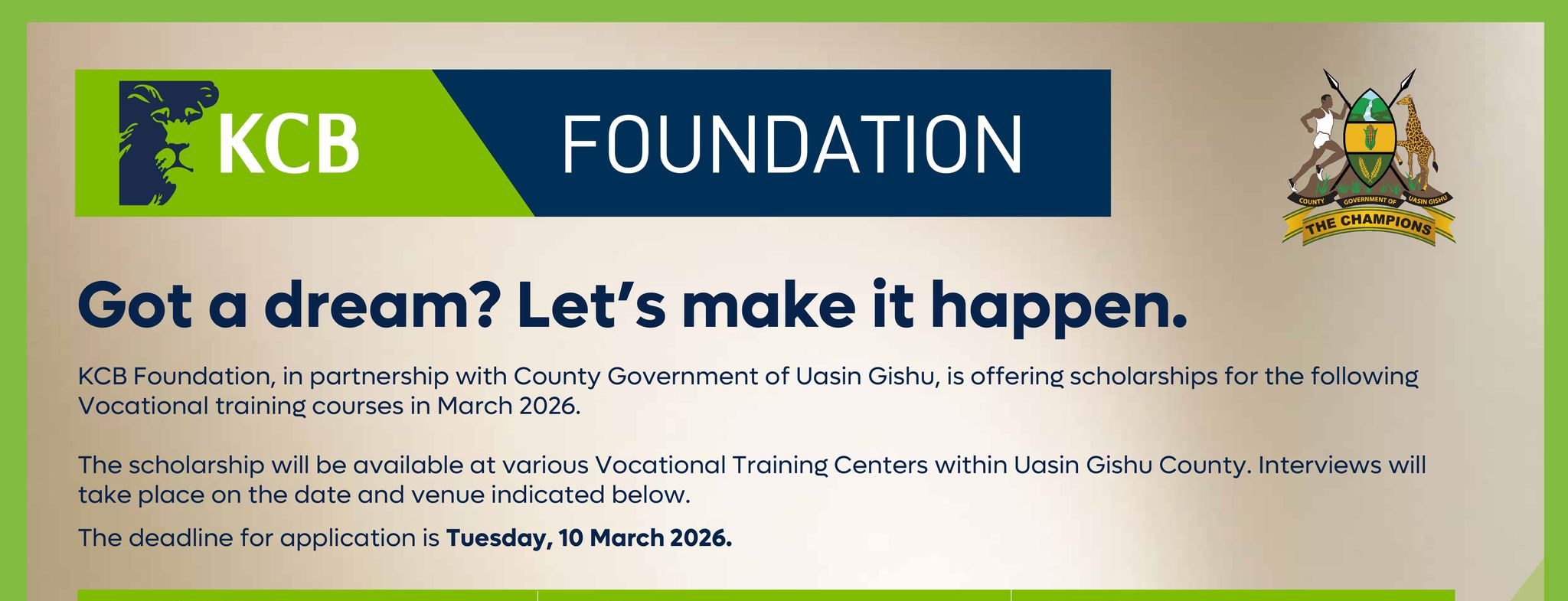

For too long, we have sold a single story of success: good KCSE results, university admission, white-collar job. That story no longer fits the realities of our economy—or our children. Technical and Vocational Education and Training institutions, teacher training colleges, medical training colleges, digital skills programmes, entrepreneurship, agriculture, and skilled trades are producing capable, independent young people every day.

We must stop pretending that university is the only respectable destination. It is one path, not the path.

Kenya desperately needs skilled technicians, artisans, innovators, and problem-solvers. We need young people who can build, fix, design, farm smartly, code, and create jobs. These paths demand discipline, intelligence, and commitment—just not the kind that always shines in written exams.

The obsession with ranking has also warped our schools. Teaching has increasingly become drilling. Curiosity is sidelined. Creativity is sacrificed. Ethics are sometimes compromised. When results are released, the focus shifts to defending or celebrating mean scores, while the learner’s long-term growth is forgotten.

Schools must ask harder questions. Did we nurture confidence or fear? Did we teach thinking or memorisation? Did we support different learning styles, or reward only one type of learner? Education does not end with results—it reveals its strengths and weaknesses through them.

The decision to repeat KCSE is another area where panic often replaces reason. Repeating is not inherently wrong. For some learners, with proper support and a clear plan, it works. But repeating out of shame, pressure, or image rarely does. Many learners would benefit more from moving forward, gaining skills, and rebuilding confidence than reliving an exam year under emotional strain.

We must also confront inequality honestly. KCSE results reflect more than effort. They reflect access to resources, teacher availability, class size, infrastructure, and exposure. Rural and marginalised schools continue to compete on an uneven field. When we celebrate outcomes without addressing inputs, we confuse privilege with merit.

ALSO READ:

Fred Ekiru: Turkana boy who defied all odds to excel in KCSE

Policy-makers should use results as a mirror, not a weapon. Where gaps appear, investment should follow. Equity should not be a slogan; it should be a budgetary priority.

Another issue we gloss over is mental health. The period after results is emotionally volatile. Learners oscillate between excitement and despair. Parents oscillate between pride and panic. Schools and communities must take mental well-being seriously. Guidance and counselling should peak now—not disappear once exams end. A calm conversation can do more good than a hundred motivational speeches.

As a country, we must redefine success—urgently.Success is not a letter on a certificate. It is usefulness. It is responsibility. It is contribution. A skilled mason running a business, a farmer adopting modern methods, a nurse serving faithfully, a teacher shaping generations, an entrepreneur employing others—these are successes. Grades may shape their entry points, but they do not define their impact.

We also need to change the questions we ask young people. Instead of “What grade did you get?”, we should ask, “What are you interested in?” “What are you good at?” “What support do you need?” These questions build futures. The former builds anxiety.

KCSE results should guide placement, not determine dignity. They should inform decisions, not close minds. When we load one exam with too much meaning, we shrink human potential.

The results are out. The numbers are known. What happens next is far more important.If we respond with wisdom, compassion, and openness, we give our young people room to grow. If we respond with panic, judgement, and obsession, we risk breaking what we claim to build.

KCSE is a chapter. Life is the whole story. Let us stop reading the book backwards.

By Hillary Muhalya

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape