The promotion interviews conducted by the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) have become something of a national joke, only that the consequences are far from funny. For many teachers who have dedicated decades of their lives to serving learners, these interviews are not only humiliating but also absurd in both content and design. We’ve turned what should be a merit-based, leadership-elevating process into a trivia contest of disconnected facts, bureaucratic hurdles, and shallow indicators of competence.

Take, for instance, the kinds of questions being asked: How many education task forces has Kenya had since independence? Who chaired the Gachathi Report? What year was the Koech Commission formed? You can almost hear a teacher stammering to recall whether it was 1976 or 1981 – not because it matters, but because it’s suddenly the question that decides their leadership fate.

Let’s ask ourselves seriously: How does knowing the number of task forces formed in Kenya qualify one to lead a school? How does naming the year of the Ominde Report demonstrate the ability to manage staff, handle student discipline, or work with BOMs and parents? This is where we go wrong – because we ask the wrong questions.

We’ve reduced leadership interviews to memory tests. What ought to be an opportunity to assess one’s capacity to lead, innovate, mentor, and transform schools has been turned into a bureaucratic theatre of facts and figures. A headship position is not about historical recall; it is about vision, resilience, emotional intelligence, decision-making, and people management. Yet, none of those qualities are tested.

Worse still, we lean heavily on years in service and job group as indicators of readiness to lead. A teacher with 20 years in the classroom is assumed to be more deserving of promotion than one with 10 – regardless of performance, creativity, or leadership potential. But we all know that years do not equal experience. Some people have repeated the same year of teaching twenty times. They’ve grown old, not necessarily wise. Others have grown in leaps within five years – by initiating clubs, mentoring colleagues, improving KCSE outcomes, leading school-wide programs, and inspiring learners. But the system doesn’t see that. It only sees the calendar.

The same flawed logic applies to job groups. Someone may have been stuck in C3 for lack of a vacancy, despite their stellar performance. Another may have been bumped to D1 because they were lucky to serve in a hardship area. But when interview time comes, those letters and numbers are treated like sacred evidence of competence. It is irrational, and it is unfair.

We must also confront the political nature of these interviews. Many teachers walk in not just underqualified, but also underprepared – because the actual process is opaque. The marking scheme is shrouded in mystery. You don’t know whether the panel will ask about Basic Education Regulations or expect you to recite Vision 2030 pillars. There’s no feedback. There’s no coaching. Just a number pasted on a list two months later – successful or not successful. That’s it.

This opacity has bred anxiety, mistrust, and resentment among teachers. Good teachers. Teachers who have given their all to learners. They feel mocked. They feel unappreciated. They feel sidelined by a system that values bureaucracy more than potential.

And while we’re here, let’s talk about how these interviews do not assess what really matters in school leadership. No one asks: How would you deal with a case of teacher absenteeism? How would you balance academic targets with learner well-being? What’s your vision for community engagement in your school? How would you handle a crisis, like a fire or a student strike? How do you mentor young teachers?

These are the questions that separate real leaders from position-seekers. These are the conversations that should define school leadership in the 21st century. Not who wrote what report in what year.

READ ALSO:

Finlay’s Trust awards KSh 8.7 million TVET scholarships to 40 youths in Bomet and Kericho

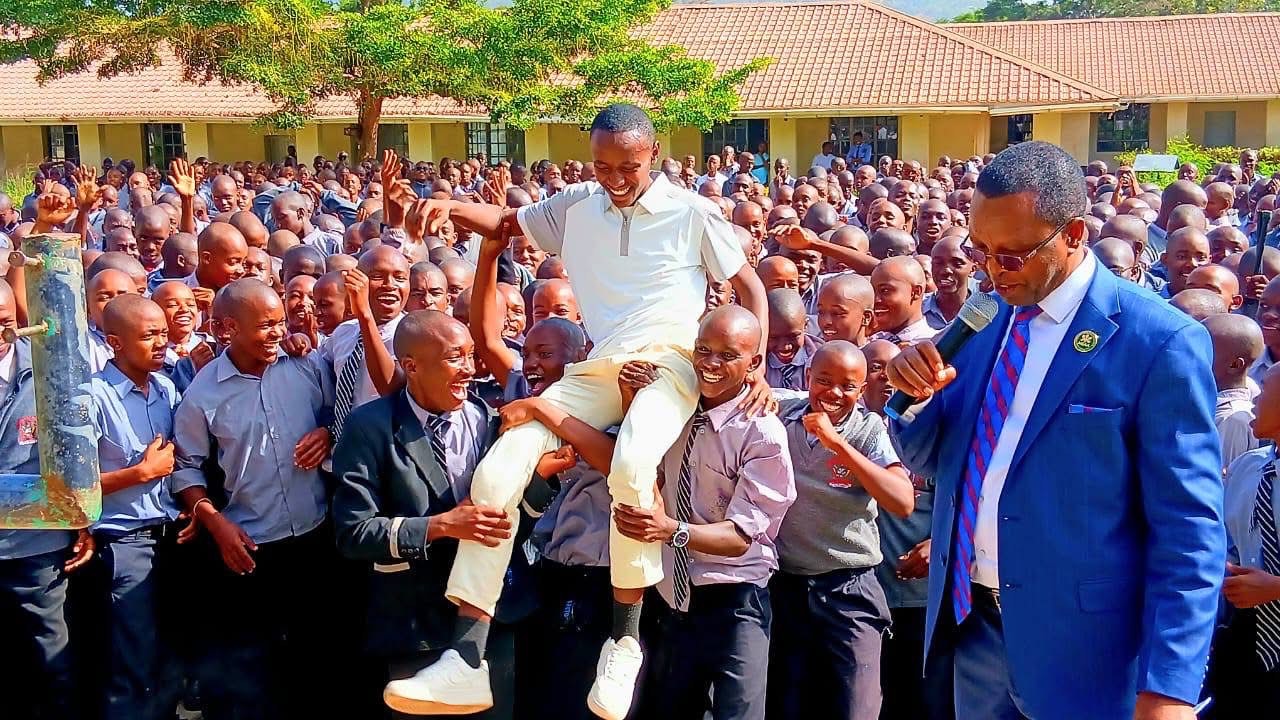

And then there’s the irony. Many of the best school leaders today – the ones turning around KCSE mean scores, reducing dropout rates, leading mentorship programs – are not necessarily the ones holding the highest job groups. They are not always the ones with the oldest TSC numbers. They are simply people who lead from the heart, with vision and values. But the system is not wired to see them. The system filters them out at the gate.

If we want to improve the quality of school leadership in Kenya, we must first fix how we identify leaders. That means redesigning the interview process to reflect modern leadership demands. It means embracing performance-based assessment, portfolios, peer reviews, and case studies – not just one-off interviews based on trivia. It is not about memory.

We need to assess communication, vision casting, stakeholder management, and innovation. We need to test how well a candidate knows the CBC rollout in practice – not just in theory. We need to know whether they can inspire teachers, mobilize resources, and resolve conflicts without escalating them. These are the soft, often invisible skills that define a great school leader – and they cannot be tested by asking how many chapters are in the Basic Education Act.

In the end, the tragedy is not just in who misses out on a promotion. It’s in the kind of leadership we institutionalize. When we ask the wrong questions, we reward the wrong qualities. And then we wonder why schools lack direction, why teachers feel demoralized, and why learners are not inspired.

If we are serious about transforming education, we must begin by transforming how we choose leaders. It’s time to move beyond job groups and task forces. It’s time to look for wisdom, not just knowledge. For service, not just seniority. For vision, not just vocabulary.

Until then, we will keep sending the wrong people into the right positions – and paying the price in stalled schools, frustrated teachers, and lost learners.

By Ashford Kimani

Ashford teaches English and Literature in Gatundu North Sub County and serves as Dean of Studies.

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.

>>> Click here to stay up-to-date with trending regional stories

>>> Click here to read more informed opinions on the country’s education landscape

>>> Click here to stay ahead with the latest national news.