Court ruling offers hope to teachers fired by TSC

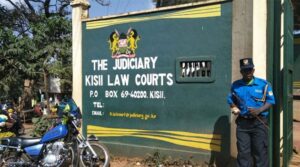

Court, in a landmark judgment that sets ground for past cases to be revisited, Principal Judge Justice Byram Ongaya ruled that the panel which heard a petitioner’s case was improperly constituted since it was not composed as per clause 119(2) of the TSC Human Resource Manual, which provides that a disciplinary panel shall comprise of at least one member of the commission, who shall chair the proceedings.

A recently ruling favoured a petitioner against the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) is likely to cause a ripple of cases touching on teachers who have been dismissed from service, if the law of precedence is applied.

Most teachers who had earlier been dismissed have got a lifeline following the court decision that saw a secretariat staff win based on the improper composition of the disciplinary panel that heard and determined her case.

Employment and Labour Relations Court (ELRC) raised concern over the manner in which the commission handled this particular case, yet the impact may open up cases going back to more than a decade ago.

In this case and according to court papers, Rose Mwende Mutisya, who was the Commission Senior Human Resource Officer, had sued TSC and Kenneth Marangu, a manager, seeking a declaration that Marangu, who chaired the disciplinary panel that led to her dismissal, lacked constitutional and lawful authority to chair a disciplinary panel and make decisions on behalf of TSC since such functions are within the exclusive mandate of the Commission.

In the judgment dated March 10, 2023, Principal Judge Justice Byram Ongaya ruled that the panel which heard Mwende’s case was improperly constituted since it was not composed as per clause 119(2) of the TSC Human Resource Manual, providing that a disciplinary panel shall comprise of at least one member of the commission, who shall chair the proceedings.

Despite TSC submitting that there was a resolution made at a meeting on May 14, 2020 that hearing of all categories of discipline cases, except for reviews, be heard by management, Justice Ongaya observed that the HR Manual was a statutory instrument under the Statutory Instruments Act, 2013.

He said the alleged delegation by the commission to the management as was done could not operate to validly change provisions of the HR Manual.

According to the Judge, the respondents in the petition, who in this case were TSC and Marangu, confirmed in their replying affidavit that the TSC HR Policies and Procedures Manual, 2018 for secretariat staff were made pursuant to provisions of section 47 (2) of the TSC Act and section 5(1) of the Public Officer Ethics Act.

“Being an instrument made under the statutory provisions, the Court finds that indeed its provisions could not be changed internally by the respondents without involving the affected persons (like the petitioner) and involving (the) Parliament as envisaged in the Statutory Instruments Act, 2013-and which has not been shown to have been done. Thus, as submitted for the petitioner, the disciplinary panel was improperly constituted, its decisions null and void. The Court finds accordingly,” ruled Justice Ongaya in his judgment.

The judgment is likely to affect a huge number of past disciplinary cases conducted by TSC county directors or other officials in the management, setting stage for petitions by thousands of teachers who might have been sacked unconstitutionally.

If this arises, the court might apply the ‘stare decisis’ doctrine, or the law of precedence, which means to ‘stand by things decided’.

When a court faces a legal argument, if a previous court has ruled on the same or a closely related issue, then it will align it to that ruling. This is where you see a judge cite: ‘In the case of…vs…’

The doctrine operates both horizontally, where a court adhere to its own precedent, and vertically, applying the precedence of a higher court.

Court favours dismissed teachers in landmark ruling

In Kenya, the Supreme Court is the highest court and its decisions are binding on the Court of Appeal, the High Court, the Magistrate’s Courts, as well as specialized courts and tribunals.

The Supreme Court would normally also follow its own decisions unless it can overrule them, so that they are set aside and cease to have the force of precedence.

The decisions of the Court of Appeal are binding on the High Court and the Magistrates Courts, while those of the High Court are binding on the Magistrate’s Courts, which do not in themselves create any binding precedent for any court.

According to the Code of Regulations, if the commission is hearing a disciplinary case at the headquarters, the disciplinary panel shall comprise of at least one member of the commission as Chair, two directors or their representatives appointed by the Commission Secretary, and in attendance an officer representing the division dealing with matters discipline.

The panel at the county level comprises of a member of the commission, the respective TSC county director or an officer appointed by the commission who shall chair the panel, an officer appointed by the county director, the county director of education or a representative, and in attendance, an officer designated by the county director to deal with matters touching on discipline.

Last year, the commission admitted that it has been losing court cases due to lack of evidence, urging all its officers to thoroughly investigate before handling any case against teachers.

Mary Njawa, who works in the Legal Affairs and Industrial Relation department, while meeting all TSC sub-county directors in 2022, advised them not to be in a hurry to dismiss any teacher, and that they should instead conduct thorough investigations before reaching a decision as that’s what’s fair to both the commission and the accused teachers.

In 2022, the commission sacked, removed and de-registered a total of 64 teachers on various charges. In October 2021, 43 teachers were de-registered and in May the same year, 52 lost their jobs. In November 2020, fifty were fired.

Kenya National Union of Teachers (KNUT) at one point suggested that the Teachers Appeals Tribunal should be revived as a judicial body outside TSC.

It argued that as per the current arrangements, TSC handles teachers’ appeals, hence an aggrieved teacher may not get justice since the employer prosecutes, judges and listens to their appeal.

By Roy Hezron

Get more stories from our website: Education News

You can also follow our social media pages on Twitter: Education News KE and Facebook: Education News Newspaper for timely updates.